Outrage flooded into the aisles of the Théâtre des Champs Elysées on the night of 29 May 1913, and spilled into the streets of Paris’s 8e Arrondissement. The premiere of Le Sacre du Printemps, a new ballet staged by Sergei Diaghilev’s Les Ballets Russes, with choreography by Vaclav Nijinsky and a pulsing, dissonant score by 31-year-old Igor Stravinsky, had incited a riot. The well-heeled patrons from the 16e, the tony, bourgeois quartier around the Trocadero Palace, howled in disgust, demanding a refund for their tickets and the heads of the men responsible for the travesty of taste that they had just witnessed, though not necessarily in that order; the bohemians from Montmartre shouted back in defence. Epithets flew, backed with fists, umbrellas and handbags. One of the greatest works of musical theatre of the young century debuted in chaos.

It was, Diaghilev gaily commented, “exactly what I wanted.”

Indeed, the modernism that Le Sacre exemplified sought to deliver, as Vladimir Mayakovsky and the Russian Futurists wrote a few months earlier, A Slap in the Face of Public Taste. Since the French Revolution of 1789 and throughout the 19th century, European culture had negotiated the contending impulses of innovation and conservatism, bracing them in an uneasy equipoise as forces of socio-economic change eroded the traditional authority and privileges of crown and church.

The Council of Vienna, concluded a little more than a week before Napoleon Bonaparte’s final defeat at Waterloo in June 1815, was supposed to have settled the map of Europe, restore the Bourbon monarchy at Versailles, and restore the “permanent” stability of the continent. Yet nothing was stable or permanent. The Industrial revolution changed everything. By the end of the 19th century, capital – not land – was the foundation of power in Europe; the capitalist bourgeoisie had emerged as the dominant class and aristocrats found increasingly that their privileges and prestige could be preserved only by playing the bourgeois economic game.

Tectonic socio-economic shifts radically altered the economy of European art. Traditionally, artists had been servants in the great noble houses and religious establishments. Kings, counts and bishops owned both the artist and his art – sometimes mere occasional delicacies, like Georg Philipp Telemann’s Tafelmusik or Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s many, airy divertimenti – but more often monuments of importance and permanence. The aristocrats of the anciens régimes, occupying a social space conceived as divinely-ordained and immutable, had owned art. The rising bourgeoisie, whose power was based on fluidity and exchange, and who occupied a social space defined by mobility and change, consumed art.

And they consumed it at a ferocious pace, opening up a vast expanse of possibilities for artists. No longer restrained by the demands of aristocratic or ecclesiastical patronage, artists – painters, sculptors, and above all composers – competed as independent contractors for a growing bourgeois art market hungry for innovation, experimentation and, often enough, titillation and thrills. The heroic, revolutionary creative genius became a familiar trope in 19th century Romantic literature and popular culture as artists from Eugene Delacroix to Franz Liszt fell over each other to press the boundaries of artistic convention in search of notoriety, fame and fortune.

In music, this meant testing the limits of rhythm, form and tonality. Ludwig van Beethoven was the great prototype. His genius had redefined the concerto and revolutionized the symphony, and set a standard for innovation that was both an invitation and a challenge to the composers who followed. Johannes Brahms famously complained that Beethoven’s complete mastery of the symphony had made his own efforts pointless: “I shall never compose a symphony! You have no idea how it feels… when one always hears such a giant marching behind one.”

Composers pushed tonalities almost to their breaking point. The conventions of western music were based on a harmonic system that demanded resolution on the tonic chord of a given key. A composition in C-major, for example, was expected to end on a chord composed of the notes C-E-G, which were all related to the basic note of the key by the tonal proportions of the harmonic series. Melodies could move freely within the coordinates of the key, and harmonies might be built on any of the chords composed of they key’s notes. A composer could even go slightly out-of-key or use dissonances, but with the understanding that the harmonies and melody would ultimate resolve in the home key.

Throughout the 19th century, composers like Brahms, Hector Berlioz, and especially Richard Wagner, discovered that they could create ever-more dramatic, thrilling music by using dissonances and going off-key more often in their works, and delay harmonic resolution as long as they dared. Wagner was particularly adept at this, building tension and drama in his 1859 opera Tristan und Isolde with a complex, dissonant chord identified with the lead character (the knight Tristan) that demanded resolution. As the harmonic drama increased, the audience held its breath waiting for, expecting a musical and narrative resolution, Wagner just let them wait… and wait some more, until finally offering the explosive delayed harmonic gratification.

Yet, for all of their willingness to experiment and push the boundaries of musical convention, the composers of the 19th century always brought their music home – resolved within the comfortable territory defined by the diatonic key and harmonic convention. Their revolutionary impulses were disciplined and restrained by the equally powerful impulse of creative conservatism. However Brahms, perhaps better than anyone, understood the implications of a half-century of tonal and harmonic innovation. Facing the possibility that the next step would be the complete abandonment of tonality, he recoiled in horror and resolved, following the completion of his great Double Concerto in A-minor in 1889, to give up composing altogether. Ultimately, he did not, but his later works betray the conservatism of a composer who found himself at the precipice and stepped back.

Others were less skittish. Indeed, by the beginning of the 20th century, virtually all of the conventions of European culture were being routinely challenged: by impressionists, expressionists, symbolists, cubists and nationalists. To some extent, this reflected the loosening grip that the economic, social and ethnic elites of Europe exerted as class warfare simmered and the “permanent” settlement of 1815 slowly unraveled in war, imperial competition and rising nationalism. Promise lay in the future of the internal combustion engine, mass production and the wonders of technology, and not the comfortable certainties of the past. From the perspective of 1912, Mayakovsky wrote that the culture of the previous century had become “less intelligible than hieroglyphics.”

There had been indications that the levee was about to break. The shifting, chromatic harmonies and fractured melodic lines of Richard Strauss’s 1905 opera Salome had left audiences and critics scratching their heads. Gustav Mahler, then the director of the Vienna State Opera could not convince the board of directors to approve a performance in the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; it was banned in London. However, official disapproval and audience resistance focused more on its libretto – based on a German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play – full of sex, incest and necrophilia.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cweQCnT97KI]

The final scene of Richard Strauss’s Salome

Mahler himself had composed a series of increasingly chromatic works throughout the 1890s and into the early years of the new century. Audiences found his Seventh Symphony utterly baffling. American critic Paul Rosenfeld denounced it as a “doubtful and bastard thing.” In France, Claude Debussy reached outside of the conventions of European aesthetics to alternative modes like the whole-tone scale to produce impressionistic harmonies as in his Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune of 1894. Of the Prélude, the critic Gustave Robert of Paris’s Revue Illustrée wrote approvingly that “the music of M. Debussy presents the peculiarity of being almost beyond any tonality.”

The final rupture came in the 1912-1913 concert season. Bookended by the premiere of Pierrot Lunaire by the Viennese composer and pedagogue Arnold Schoenberg on 16 October and the scandale of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps on 29 May, the season heralded the utter collapse of European music and the emergence of modernism.

Schoenberg had already acquired a reputation for being an enfant terrible – some would say antichrist – of European music. An audience for his highly chromatic Five Orchestral Pieces at the London proms in the summer of 1912 “tittered and laughed outright” at its searching, often dissonant harmonies and shifting timbres. Neither the audience, nor the reviewer from The Musical Standard knew quite what to make of the performance. “Mr. Schönberg is one of those unfettered persons who will not hear of rules,” he wrote. “No form, no lay-out, no development of ideas, no ideas that can be distinguished from the crudest, uncontrolled sensation, can be discerned in these ‘works.'” The premiere of Pierrot at Berlin’s Choralion-Saal a few months later signaled that Schoenberg was prepared to go much further than even that.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O5DNxRG2-ow]

“Mondestrunken” from Pierrot Lunaire

A setting of 21 poems by Belgian symbolist poet Albert Giraud, Pierrot Lunaire was a radical work. It was scored for an unconventional chamber octet and a vocalist performing in a novel part-sung, part-declaimed style called Sprechstimme “It abounds in the most extraordinary sounds, and is said to exceed Schönberg’s previous works in ‘advancement,” The Musical Times sniffed. “Serious critics state, however, that it has made an absolutely novel (if somewhat baffling) impression.”

In the Revue Française de Musique William Ritter, normally a champion of radical music, had a hard time giving the work a favorable review. “I am perplexed by the evolution of this disconcerting music,” he wrote, “and I come at it with very few clear ideas.” It was groundbreaking to be sure, and Schoenberg was one of the new heroes of modern music, but “is it beautiful? I don’t know,” Ritter almost audibly sighed. “Does it have its beauty. I am convinced, but I cannot yet define it.”

J.H.G. Baughan in The Musical Standard disagreed, claiming that “Schönberg has thrown overboard all the sheet anchors of the art of music. Melody he eschews in every form; tonality he knows not, and such a word as harmony is not in his vocabulary.” Baughan wasn’t alone, citing a New York critic who described Pierrot Lunaire as “the greatest musical monstrosity that has been perpetrated during the present generation upon a long suffering public.” Otto Taubmann wrote that “if this is the music of the future, then I pray my creator not to let me live to hear it again.”

Pierrot remained the object of European music lovers’ outrage throughout the season. Schoenberg’s partisans – other composers, the radical artists inhabiting the demimondes of Paris and Berlin, Futurists who sought to tear European culture and civilization down around their ears, even a pre-teen Frankfort gymnasium student named Teo Adorno – recognized it as a masterpiece. Music had suddenly and irrevocably changed. Schoenberg’s audacious work was debated, derided and defended for seven months in newspapers, salons, seminar rooms and concert hall foyers across Europe.

And then came spring.

Stravinsky was already the toast of Paris, recognized as a daring, if baffling musical genius. He had come to Paris from Russia in 1910, by way of Switzerland, to compose the score for The Firebird, a ballet staged by Diaghilev and choreographed by fellow Russian Michel Fokine. Diaghilev had built a considerable fortune and a formidable reputation as an impresario by giving Paris audiences what they wanted – beautiful dancers in exotic productions with the faint reek of sex and transgression. Russian composers like Alexander Borodin and Nicolai Rimski-Korsakov provided music suffused with strange oriental tonalities for productions based on Russian folklore, calculated to appeal to Parisians’ taste for the primitive and bizarre. Paul Gaugin’s bare-breasted Polynesian maidens, and Amedeo Modigliani’s alluring, Africanized erotica had shown that exotic sex would sell, or at least grab headlines.

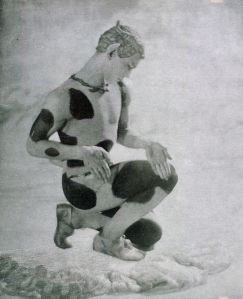

Performances of Les Ballets Russe were invariable sold out, and its dancers were celebrities, breathlessly followed in the press and mobbed in the streets. The biggest star was Vaclav Nijinsky, a sinuous, androgynous 22-year old whose short ballet L’après-midi d’un faune, to music by Debussy, left its audience speechless. The Firebird had been an enormous success, and Pétrouchka, with music by Stravinsky, choreography by Fokine and with Nijinsky in the lead role, had dazzled audiences in 1911.

For the 1912-1913 season, Diaghilev planned to stage a production that would eclipse everything that had come before. Stravinsky had been sketching an idea for a ballet on “Pictures of Pagan Russia” and Diaghilev recognized its potential. He knew Parisians would go wild over the sexually-charged sacrifice of a young girl. The composer began collaborating with costume and set designer Nicholas Roerich to produce the extravaganza. With some misgivings, Diaghilev agreed to let Nijinsky choreograph the ballet.

Le Sacre du Printemps opened on 29 May 1913. The music began with a haunting melody played on the bassoon – at a pitch so high that few members of the audience could identify the instrument. The curtain rose slowly, to reveal a tribe of pagan Russians beginning their “Adoration of the Earth” to appease their gods and welcome spring. Before long, the music became increasingly, pulsingly rhythmic, with the orchestra eschewing melody for dissonant percussive chords. The woodwinds shrieked, the strings pounded in a relentless rhythm as the dancers flailed and stamped. This was a new kind of music and a new kind of ballet. Patrons expecting Diaghilev’s usual menu of sensuousness, sex and titillation were horrified.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jF1OQkHybEQ]

The Joffrey Ballet’s reconstruction of Nijinksy’s choreography

The scandal of Le Sacre dominated the press, pushing the memory of Pierrot – at least for the moment – to the back pages. The Revue Française de Musique called it a travesty. “Massacred, as well, because it seemed monstrous to more than one art lover to celebrate spring with Mr. Nijinsky’s epileptic convulsions and the painfully discordant music,” the reviewer wrote. Although he condemned the “ridiculous” choreography out of hand, the reviewer made a supreme effort to appreciate Stravinsky’s “extraordinary” music. “It is certainly far beyond the ordinary limits of discord,” he continued. “It is sometimes terribly ugly, I would say it certainly seems so to us people of 1913.” Carl Van Vechten agreed, denouncing Stravinsky as a brutish primitive who used “barbaric rhythm, without any special regard for melody or harmony.” Primitive, perhaps, but the Revue Française de Musique reviewer wasn’t sure if that was such a bad thing. Could it be a “premature specimen of the music of the future,” he mused? “Yes, if the current evolution towards increasing complexity must continue, both rhythmic polyphonic and instrumental complexity.” At least, he wrote, the music might not seem so strange by 1940.

Indeed, Le Sacre and Pierrot were the touchstones of an aesthetic and cultural revolution that swept through Europe and the Americas is the 20th century. The boundaries which had contained composes for centuries were irrevocably ruptured and in the following years and decades, as the “immutable truths” of European society and culture collapsed in revolution, war and genocide, music became increasingly radical. Alban Berg, Anton Webern, Bela Bartok, Ernst Krenek, Henry Cowell and others pushed music into realms that not even Stravinsky nor Schoenberg had imagined and, even though both would recoil in the 1920s at the seeming chaos they had unleashed, there was no going back.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOTjyCM3Ou4]

Le Sacre du Printemps, as choreographed by Pina Bausch